How Algorithms Shape Financial Institutions

With the rise of a digital age in the realm of global finance, financial institutions have incorporated various Information technologies into their structure, thereby changing how they interact with their customers. In the nineteenth century, the financial markets were based on social groups and networks of interpersonal trust. [1] The question of whether or not one might receive a loan from either a bank or a money lender was based on factors such as one’s payment history, the social group they belonged to, word-of-mouth referrals, home visits, etc. [2]

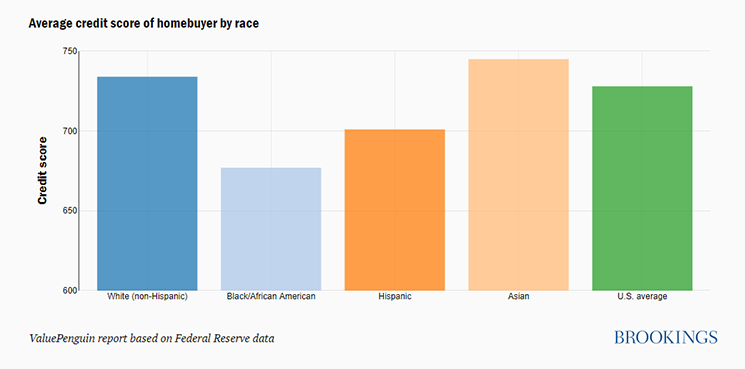

The adoption of algorithms meant that the reputation-based, qualitative assessments mentioned above were replaced by quantitative ones based on data analysis. The results of this data analysis are known as credit scores and based on a client’s credit score, a bank can decide on whether or not to provide them with a loan[2]. This AI-based approach seems like the way to go to eliminate gender, racial and religion-based bias and get fairer, more accurate credit scores. But this is not what happened. Rather than eliminate bias, this model elevated it. This might happen when the historic data that is used for training the model or the programmers who make and train these models are themselves biased, albeit unintentionally. Let us consider the example of the US. Job security, earnings and criminal records are important factors that affect one’s credit score. This means that the racial groups that were the subject of inequalities like unequal pay, unfair job termination, wrongly convicted in courts, etc. got lower credit scores[3]. This in turn limits their access to different types of loans and lower interest rates. This bias is shown clearly in the figure below.

There have also been recorded cases of gender bias in these models. Apple’s co-founder Steve Wozniak despite having a joint account with his wife and the same high limits on cards could borrow ten times the amount his wife could on Apple Card. In some cases, even when the woman had a better credit score, her male counterpart was granted permission to borrow 20 times the amount that she was permitted [4]. Even the zip code in which you reside may affect your credit score. This means that poorer neighbourhoods generally tend to have lower credit scores. Further, marital status and age also might affect your credit score. So zipcodes catering to families or older people tend to have a higher credit score.[5]

Other than banks, insurance companies also started using algorithms but it has its own set of challenges. In the US, a study found that a major health care risk-prediction algorithm demonstrated racial bias. The patients labelled high-risk by the algorithm can avail themselves of insurance benefits. But since the algorithm used previous healthcare spending of the patient as the benchmark, the algorithm put white patients at a higher risk than black patients even when they spent the same amount. This bias forces black patients to spend more than their white counterparts. The reason for this cost disparity might be due to the correlation between race and income: people of colour are more likely to have lower incomes. Due to this bias, black patients lower-quality care and have lesser trust in doctors they feel are biased.[6]

Investment firms have also started using algorithmic trading in the stock market, thereby replacing human traders, giving rise to a market where most participants are computer algorithms. These algorithms buy and sell shares based not just on their current interaction with other algorithms but also on how people, organizations, algorithms and machines interacted in the past[7]. With more and more financial institutions adopting algorithms for various purposes, it becomes important to ensure that these algorithms are as bias-free as possible. This might be achieved by algorithmic transparency (telling a customer which elements were responsible for making the decision) and training the algorithmic models on less specific information (not using gender, race, religion, etc)[4].

References:

[1] Pardo-Guerra, j. p. (2013). “trillions out of ones and zeros: the sociology of finance encounters the digital age”. in digital sociology: critical perspectives. (pp. 125-138). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

[2] The Origin of the Credit Score, Lindsay Konsko, August 2014

[3] Reducing bias in AI-based financial services, Aaron Klein, July 2020

[4] Sexist and biased? How credit firms make decisions, Kevin Peachey, November 2019.

[5] What Your ZIP Code Says About Your Credit Score, Nicholas Cesare, February 2019

[6] Racial Bias Found in a Major Health Care Risk Algorithm, Starre Vartan, October 2019

[7] MacKenzie, Donald. (2018). “Material Signals: A Historical Sociology of High-Frequency Trading”. in American Journal of Sociology.