Surveillance Technologies: Boon or bane?

In his book “Surveillance Unlimited: How We’ve Become the Most Watched People on Earth”, Keith Laidler said, “spying and surveillance are at least as old as civilization itself”. Surveillance is the act of gathering information about your subjects, supervising their actions and using this information to understand their behaviour. With the rapid growth of technology, more and more surveillance societies are emerging across the world. These societies function based on the collection, recording and analysis of their citizen’s data. This information is collected by governments and businesses to govern, regulate or influence their citizens. Studying the impact of surveillance on a society allows us to question and evidence its impact on the social fabric on grounds of discrimination, trust, accountability, transparency, access to services, mobility, freedoms, community and social justice. This is especially important considering that information processing which takes place as a part of governance or management never takes place on an even playing field since it involves putting the surveilled subjects at the mercy of the surveillant. The interests of some citizens might be served while others might be marginalised based on who the surveillant is, making the entire process prone to bias based on numerous factors such as gender, economic class, religion, etc. to name a few. Further, considering the generating and processing of a gigantic amount of data for each citizen and the silent and easily transferable nature of data across states, countries, etc. it is difficult to identify the surveillance much less analyse and study its impact[1].

The implications of surveillance could be far-reaching as explained by Foucault’s panopticon. The panopticon describes a circle formed prison building with cells having one prisoner each with a tower in the middle for the guard to observe them. The construction was such that the guard standing on the tower can see the prisoner but not the other way around, leaving the inmates with a permanent sense of visibility. After an initial period of consistent supervising and prompt punishments, the guards noticed that the prisoners began to self-regulate their behaviour, making it possible to extensively record a prisoner’s conduct. This is what surveillance looks like on a large scale - an “infinite” panopticon - discouraging subjects from rebelling against those in power by the principle “power should be visible and unverifiable” coined by Bentham. This reflects a change in how power is exercised in society from ‘sovereign power’ which is to control under the threat of physical violence to ‘disciplinary power’ which is to control under the threat of constant monitoring and surveillance of the citizens. Further, Foucault argues that the use of this disciplinary power is not just restricted to the prison system but can be extended to other parts of society. Some of the most common examples of surveillance are the use of CCTV cameras in public places, performance monitoring in workplaces, tracking of health vitals by healthcare professionals or digital technologies like smartwatches, etc. which causes people to develop a conscience and self regulate just as explained in the prison experiment[2]. Similar results were concluded from Milgram’s experiment. In the experiment, subjects chose to obey orders issued to them even when they went against their moral conscience. While not all subjects in the Milgram’s chose to go through with their respective orders, most people might not have the resources to go against a higher authority and hold their own, resulting in them completing their jobs out of compulsion [3].

One of the main reasons for the widespread adoption of Artificial Intelligence(AI) into surveillance technologies is to detect and report high-risk scenarios in real-time so that action can be taken right away. It is being incorporated into video surveillance networks to minimize risks, maximize crime prevention and save lives. In the past, due to the limited storage capabilities at the time, video footage was archived for a short time before being overwritten by much more recent footage. But today, with the development of technologies like cloud storage, machine learning, video analytics and deep learning, the model uses these massive volumes of data generated by the Internet of Things (IoT) ecosystems to establish meaningful patterns from the data and then translate these patterns into insights to defer crime strategies. AI systems make use of behavioural analytics to recognize perilous situations based on the body language of the people in the scene. They are also used to detect and alert the nearest authorities about fugitives. The usefulness of AI-based video analytics is not just restricted to preventing crimes. For store owners using surveillance cameras, these analytics apart from alerting the security about shoplifters can also provide meaningful insights about visitor flow during the open hours, product display activity, dwell time per customer and hotspots in the store. This might help store owners decide on the products to restock or structure the store in a way that maximises customer traffic. Further, smart cities are using intelligent sensors to capture data and formulate appropriate responses as events unfold[4]. Their usage here can range from controlling traffic flow and catching jaywalkers to giving mini recommendations at local restaurants, payment and identification process using facial recognition and even to rationing of toilet paper in public toilets to curb wastage![5]

Despite its numerous benefits, AI surveillance has its own set of challenges. Poorly-trained algorithms might incorrectly classify innocent people as wanted fugitives and the system might not always draw logically coherent inferences from densely populated scenes[7]. There might also exist some unintentional biases based on the economic class of the citizens in the sense that business portals send targeted ads based on their ability to spend. This means there might be a chance that the products and services that are suggested to different citizens will be different[1]. The job of these surveillance devices is not just restricted to preventing crime and could be extended to predicting them too. This gives the surveillant a significant power to detain “suspicious-looking” citizens just based on the face value. Although developed to keep the citizens safe, these technologies make identification and monitoring of marginalised groups much easier, which is especially harmful if the surveillant has hostile intentions towards these groups[7]. There are an estimated one million Uighur Muslims and other Muslim groups detained in internment camps in the western Xinjiang region said to be undergoing “re-education” programmes. Uighur Muslims make up about 11 million of 26 million people in the Xinjiang region and there is growing evidence of oppressive surveillance against the Xinjiang targeting Muslims who are forced to give DNA and biometric samples. A number of these Muslim families have gone missing and former prisoners live to tell stories of the physical, mental and psychological torture in these camps. Rights groups inform that the people in these camps were forced to learn Mandarin Chinese and criticise or renounce their faith[8].

Another important challenge to consider is the privacy issues that come with surveillance. Citizens are aware that they are being monitored online due to events such as the Snowden leaks and the Cambridge Analytica scandal. It does not matter whether you are an innocent citizen or a criminal, in the wrong hands, the data collected through these technologies can be used against you[7]. Once an AI system identifies you, it cross-references all your details like social security number, social media handles, bank account details, etc. to name a few[5,6]. Hence, guarding this data is of the highest priority. If such data is poorly handled, it will leave the surveilled citizens vulnerable to stalking, hacking, etc[9]. The scope of these surveillance technologies is not just restricted to public spaces but is starting to increasingly infiltrate private spaces changing the traditional sense of public and private spaces. This involves automated monitoring of entry into residential buildings, the frequency of visitors per apartment, the in-time and out-time of residents and visitors to name a few. Further, the presence of boards that say “Constant surveillance” in public spaces and not finding the related surveillance devices might bring about a sense that they are being monitored constantly from a direction they cannot fathom and this might cause them to self-regulate. This behaviour of the citizens causes them to automatically self-regulate even in their “traditionally” private spaces as mentioned in the panopticon experiment mentioned above[5].

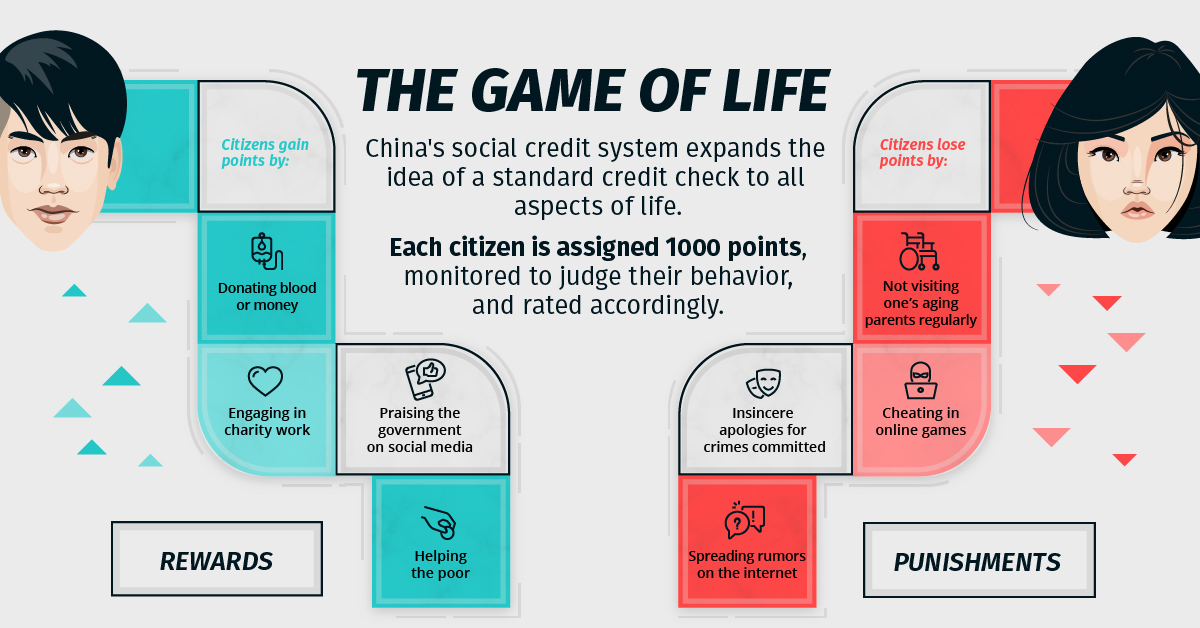

China, which has the largest video surveillance network in the world, proposed launching its social credit system as a state surveillance infrastructure to determine the ‘trustworthiness’ and ‘creditworthiness’ of its citizens[11]. Under this system, every activity of each citizen is monitored and based on the state-mandated nature of these activities, the citizen’s social credit score is appropriately increased or decreased. This is eerily similar to the episode “Nosedive” from the dystopian television show “Black Mirror”. In the episode, the characters rate every interaction that they have with another person and based on these ratings, an ‘average popularity score’ is calculated. Those with higher ‘popularity’ are given special promotions and privileges and the ones with lower ‘popularity’ are treated as second class citizens. This is exactly what is happening in China but instead of the citizens rating each other, the state rates them all based on the surveillance data, almost like a futuristic vision of Big Brother[11]. Those with higher social credit scores can rent cars without a deposit, skip hospital queues, etc as a reward for being a “trusted” citizen. The citizens who are critics of the government and its policy are automatically given a low score and deemed “untrustworthy”[10]. The government rolled out a travel ban on people with low credit scores. These low credit citizens were banned from booking airline and train tickets[12]. Certain universities or schools may prevent students from enrolling if the respective student’s parents social credit is low. Employers can refer to the debtor blacklist while making an employment decision. Further, some positions such as government jobs are only open for people with a certain social credit score. Businesses with poor credit score might be subjected to frequent inspections. There’s also a culture of public shaming prevalent against those with low credit scores. This can make it difficult for businesses to build relations with local partners who can be negatively impacted by their partnership[14]. These measures were taken by the government to incentivise the citizens to follow the law. The idea behind implementing this system is similar to a meritocratic system. You do a good deed, your social credit increases; similarly, you do a bad deed, your credit decreases correspondingly[5,6]. This idea seems to work well in theory. But in practice, this system is much more complicated. The idea of good and bad deed is determined by Chinese morality and the Chinese legal system. If even one of them is not sound, the social credit system will take a turn for the worse[5]. This is especially the case for China’s legal system, where the communist rule has many a time trumped universal legal values that the country accepted in principle. Even to talk freely about constitutional reform within the sheltered confines of universities and academic journals, is not a safe endeavour. And discussion of judicial independence from the Communist Party at the central level is a forbidden subject. This gives the Communist Party ultimate autonomy over the law-making process with no legal institution that can question them[13]. Further, it is well within their power to blacklist those who speak against the leadership, which might cause the citizens to self-regulate to avoid the repercussions of getting caught on the bad side of the state. Apart from being a prominent user, China is also one of the biggest producers and exporters of these AI-powered technologies[15].

Surveillance can come in many forms. Apart from China, other institutions like insurance companies, banks, etc. use past credit history and actions as a way of deciding our worthiness. So, this dystopia is not too far away. What started as institutional technologies to curb criminal behaviour are turning into abstract technologies of self where the citizens are regulating their behaviour to not fall prey to surveillance. This is why it is of utmost importance that policymakers and governments act cautiously as the need for adapting surveillance technology becomes necessary for societies around the world. The surveillants need to keep in mind the repercussions that might result from deploying these systems and attempt to mitigate some of the problems mentioned above

References:

- An introduction to the surveillance society

- K. Thompson(Sept. 2016), Foucault – Surveillance and Crime Control

- Milgram, Stanley (1963). “Behavioral Study of Obedience”. Journal of Abnormal and

Social Psychology. 67 (4): 371–8.

- J. Bonoan, A. Ataev(Mar. 2020)- AI and Specialty Analytics are Changing Video

Surveillance

- China: “the world’s biggest camera surveillance network” - BBC News

- How China Tracks Everyone- VICE News

- The Future of AI Surveillance Around the World (Aug. 2019)

- R. Hughes(Nov. 2018), China Uighurs: All you need to know on Muslim ‘crackdown’

- J.L. Kent, C.A.Sottile,M.Cappetta, (Dec. 2016)Uber Whistleblower Says Employees

Used Company Systems to Stalk Exes and Celebs

- Mistreanu, Simina. “China is implementing a massive plan to rank its citizens, and

many of them want in”. Foreign Policy. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- R. Botsman, (2017)-Big data meets Big Brother as China moves to rate its citizens

- S. Liao,(Mar. 2019) China banned millions of people with poor social credit from

transportation in 2018

- J. A. Cohen (Feb. 2016) - A Looming Crisis for China’s Legal System

- D. Donnelly, (Apr. 2021)-An Introduction to the China Social Credit System

- K. Buchholz (Aug. 2020), Chinese Surveillance Technology Spreads Around the World